This post is part 14 of the series Fresh Foundations which is about helping you create a sustainable and joyful language learning routine. If you subscribe, you’ll get access to the previous posts and receive a new one every weekday in January.

If that sounds like something you’re ready for, subscribe today to get full access to all the posts.

Focus on Form

Over the last two weeks, we’ve focused on developing our receptive and productive skills: reading, listening, writing, and speaking. These skills form the foundation of communication, but to use them effectively, you also need the tools of grammar and vocabulary.

This week, we’re turning our attention to those tools. Today, we’ll explore the theory behind grammar and vocabulary learning and answer common questions to help you decide how to make the best use of your time and effort.

Do I Really Need to Study Grammar and Vocabulary?

What comes to mind when you think about learning a language? For many people, it’s sitting in a classroom, studying boring grammar rules, and memorizing endless vocabulary lists.

This isn’t surprising, as many of us were first introduced to language learning through outdated methods like grammar-translation. While memorizing declensions and conjugations might be helpful for translating “dead languages” like Latin or Ancient Greek, these methods don’t work as well for learning to communicate in modern languages.

In response to these limitations, language teachers and linguists developed approaches like the audiolingual method. This method focused on listening and repeating phrases without studying grammar directly. While some learners succeed with this approach, it requires massive exposure to the language which is far more than most people can achieve with just a few hours of study per week.

Today, most teaching methods combine different techniques, often including Focus on Form. This approach involves paying attention to grammar and vocabulary while using the language in communication. It helps learners balance fluency, accuracy, and range, making it a practical and effective way to learn.

Focus on Form is supported by theories such as the Noticing Hypothesis, Interaction Hypothesis, and Skill Acquisition Theory, which you learned about in last week’s post on productive skills. These theories show that noticing and practicing specific language features in meaningful contexts can significantly improve language learning outcomes.

Is Learning Grammar Rules Helpful?

The short answer: yes, but not on its own. There are two ways to learn grammar:

Implicit Learning: You learn rules naturally through exposure, often without realizing it. Children, for example, usually learn their first language this way.

Explicit Learning: You consciously study and understand rules. For adults, explicit learning can speed up progress. For example, knowing that adding -ed to regular verbs makes the past tense lets you talk about the past immediately, instead of waiting to hear every verb used in context.

An anecdote might illustrate this better:

I had a colleague, Natalia, who was learning Spanish entirely through implicit learning. She spoke extremely fluently, but it was sometimes difficult to understand exactly who she was talking about or when an action happened because she didn’t want to memorize conjugations. It took her years of living and working in Spain to fix these problems with accuracy and communicate more effectively.

While waiting to speak until you can do it perfectly is a big mistake, relying solely on "picking up" a language without any study can also hold you back.

As adult learners, one of our greatest strengths is the ability to understand and apply complex concepts like grammar rules, so why not use that to our advantage?

Research supports the benefits of explicit learning. For example, Norris and Ortega (2000) found that explicit instruction led to better long-term results than implicit methods. However, studying grammar is not enough on its own. You need to combine it with meaningful practice (DeKeyser, 1998).

This brings us to two important types of knowledge: declarative and procedural.

Declarative vs Procedural Knowledge

These two systems explain how we store and use language.

Declarative Knowledge: This involves facts and rules, such as knowing that adding -ed to a verb makes the past tense. It’s the knowledge you consciously think about and recall when speaking or writing.

Procedural Knowledge: This is the ability to use language automatically, like forming sentences or using grammar correctly without consciously thinking about the rules.

Declarative knowledge is often the starting point for adults learning a language. For instance, understanding how to form the past tense allows us to describe past ev ents. However, knowing the rule doesn’t mean we’ll automatically apply it correctly. Factors like our first language and where we are in our language learning journey can influence how easily we can put the rule into practice.

To bridge the gap, we need to develop procedural knowledge by repeatedly using the rule in meaningful situations, such as speaking, writing, or listening to real conversations.

It’s similar to learning to drive a car with manual gears. You might understand the theory—when to change gears and how to do it—but it takes practice to develop the muscle memory needed to let off the gas, push the clutch, and shift smoothly. Only through repetition does it become automatic.

By recognizing how declarative and procedural knowledge work together, you can better understand why combining study with practice is essential for lasting progress.

What About Vocabulary?

While grammar is essential for structuring your sentences, vocabulary is the foundation that brings meaning to your communication. Learning new words is obviously at the heart of language learning, but it’s not just about memorizing long lists; it’s about encountering words repeatedly and using them effectively.

Research highlights just how important repetition and practice are for building vocabulary:

You need 10–20 encounters with a word to fully learn it (Nation, 2013).

Learners retain only 5–10% of new words from each reading or listening session (Schmitt, 2008).

Spaced repetition can boost recall by up to 80% (Ebbinghaus, 1885).

These findings show that vocabulary learning, like grammar, requires deliberate effort and consistent exposure. But what’s the best way to approach it?

How should I record new vocabulary?

My English learners ask this a lot, and I think it’s because they’ve heard a variety of opinions on the matter.

I know teachers who recommend:

Noting down the word in and a definition in the target language

Noting down the word in the TL and a translation in L1 (learner’s first language)

Noting down the word, translation, definition and example sentence

Noting down the word, pronunciation in IPA, example sentence, definition, collocates, etc.

Nothing specific-let learners figure out what works for them on their own.

I have been all of these teachers. 😅

For me as a learner, I prioritize consistency over intensity. If something is too much of a hassle, I won’t do it, so I look for ways to get the most out of any effort. So here are the guidelines I use for myself:

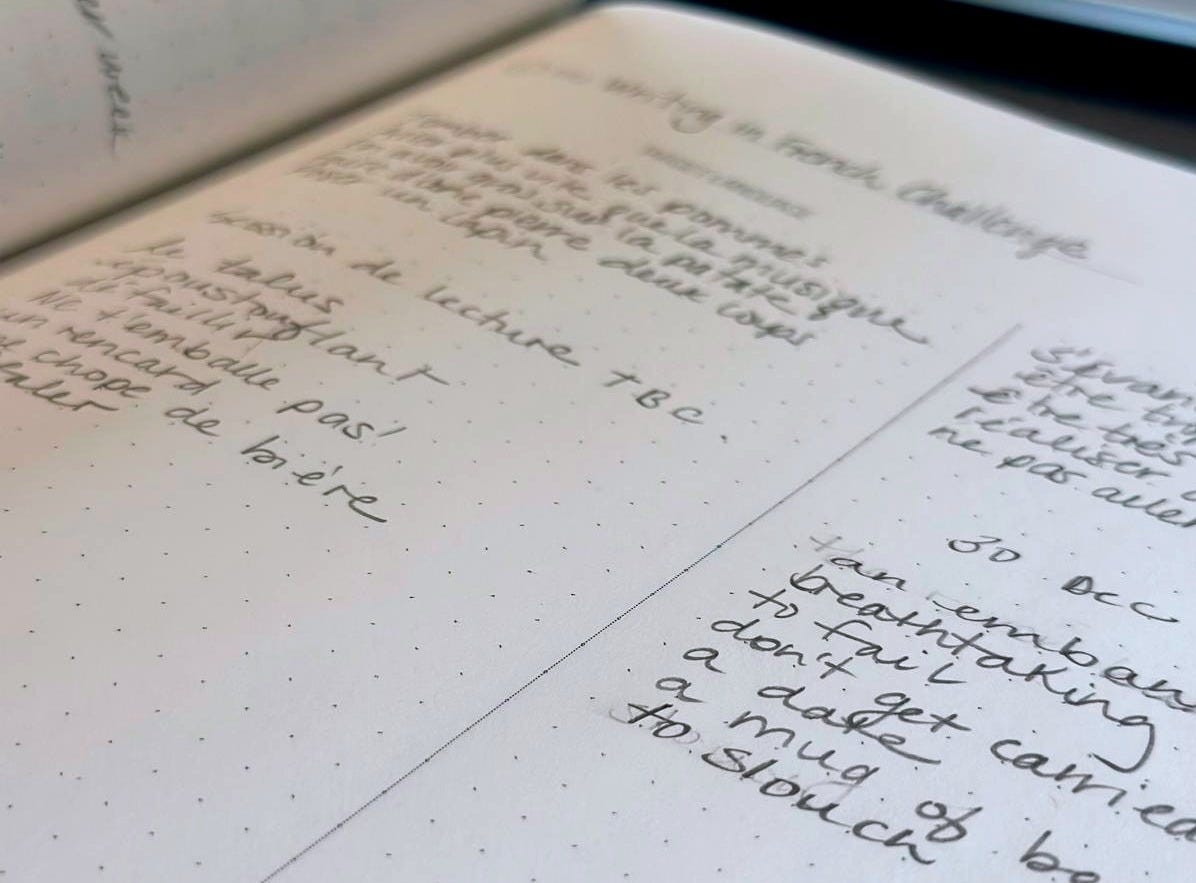

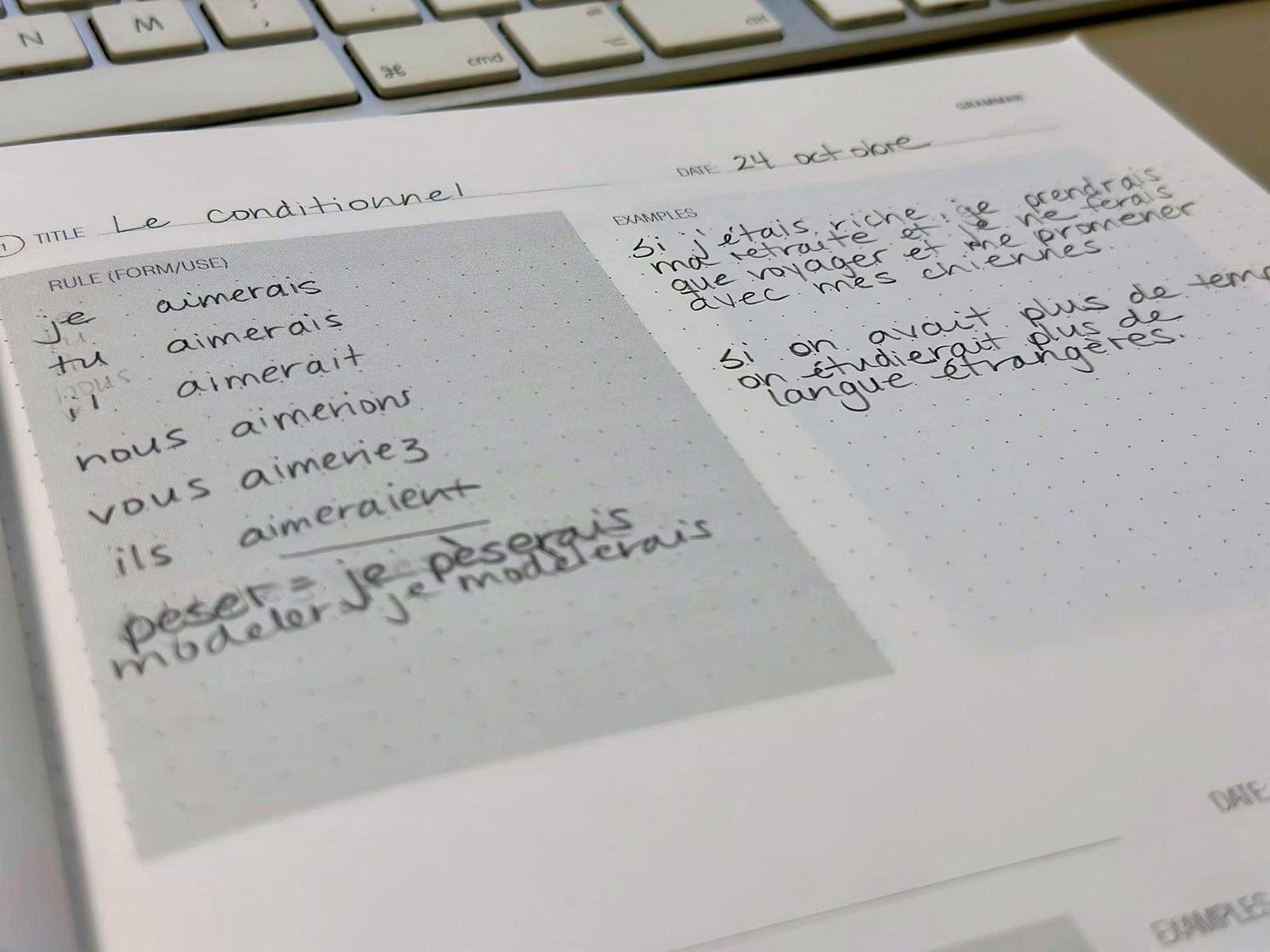

Don’t just write the translation in the margins. At minimum copy the new word and translation into a dedicated section of your notebook for regular review.

Focus on chunks. Don’t just write “decision.” Write “make a decision” or “come to a decision.”

Write examples. Create personal sentences using new words or phrases.

Use your new vocabulary. When journaling, refer to your list of new words and include as many as possible in your writing.

If you’re serious about learning new vocabulary and making progress, keep some form of structured notes. You might be surprised at how effective simply writing things down can be!

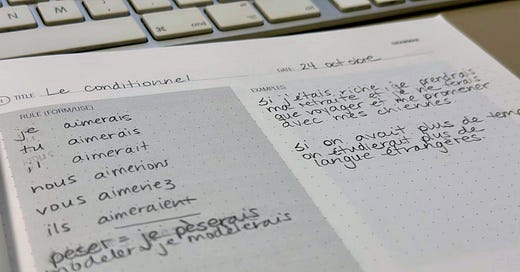

(That’s why I’ve created a vocabulary notebook and a language learning notebook with a vocabulary section. Using resources that you love can give you a little extra boost of motivation.)

This Week

This week, we’ll build on these ideas with practical strategies to help you turn theory into action.

Vocabulary Techniques: Discover strategies for finding and learning new vocabulary to expand your range and sound more natural.

Rebuilding Texts: Learn an easy method to reconstruct texts, making grammar practice more meaningful and useful.

Activating Knowledge: Focus on developing your procedural knowledge.

Create Your Routine: On Friday, get a tool to help you design your own study routine, so you can keep improving in a way that works best for you.

By the end of the week, you’ll have clear, actionable steps to take your language learning further!

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations. This was long post. 😅 If you’ve found it useful, please give it a like, leave a comment or share it. The rest of the posts this week will be much shorter.

References

DeKeyser, R. M. (1998). Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing second language grammar. Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research.