María

Years ago, I had a 12-year-old student named María in my pre-intermediate English class. María had been at the language school for half her life and was starting to lose her motivation.

Even though she always communicated in English, María often seemed distracted. She was the type of student who was always “looking for her pencil,” shoved her crumpled papers into her bag, never read or listened to instructions and did her homework with her brain “off” (i.e. just enough so that I couldn’t call her mom).

As you would probably guess, María was routinely getting 4/10 on formative assessments. I spoke to her mom, who just shouted at her for being lazy. (I now suspect María has undiagnosed A.D.D. but I didn’t think of that possibility at the time.)

Something needed to change if María was going to pass this course. However, what ended up happening was completely unexpected.

I always gave “fast finishers” another activity to work on. Most of the time, I’d give them little vocabulary cards to quiz themselves or conversation questions to ask their partner. On this occasion, I gave María a set of about 10 sentence transformation cards that have an exercise on one side and the answer on the back.

One Monday afternoon, I saw María doing a little celebration after completing each card. Then she called me over. “Teacher! Teacher! I got all the cards right!”. I said something like: “Nice work, let’s see if you can do them in the other direction.” I let the rest of the class get off task or do whatever they wanted, while María continued with her little cards.

Something changed ever so slightly after that moment. The next class, she raised her hand to answer a question. Later, I was able to use her as an example of “clear pronunciation” for the rest of the group (she does have a very nice accent). And she started doing her homework-but now, with her brain “on”.

She got a 7/10 on her final exam and went on to pass the B1 Cambridge exam. Of course, I told her mother that María’s improvement was thanks to the effort she put in. That wasn’t a lie, but it wasn’t the whole truth. I think she needed to get a few things right to make the effort seem worth it.

While it may be too much to attribute María’s success to this one turning point event, I’ve heard similar stories from expert level language learners.

Turning Points

In my latest podcast episode: How to Learn a Language: The Secret Ingredient, I share some of these stories.

Carlos, for instance, discovered he could follow The Goblet of Fire without subtitles, and Francisco realized his potential when classmates wanted to copy his work. Both found their turning points through small but meaningful successes.

What has worked for these learners may not be the exact fit for you, but the idea of building momentum and learning to enjoy the process can still apply.

The Upward Spiral

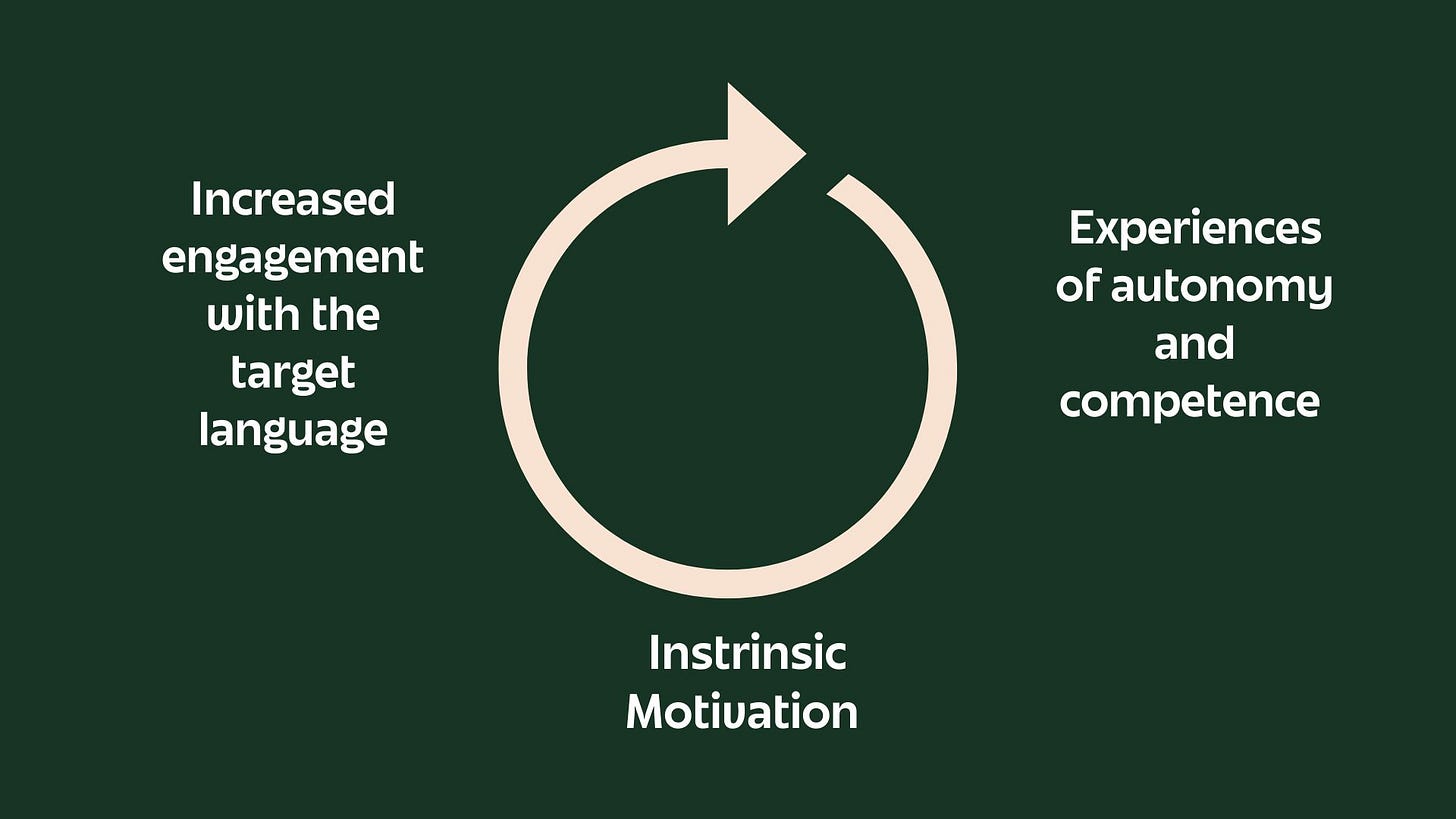

This is what I like to call the upward spiral of language learning. Research shows that feeling a sense of independence and accomplishment can spark the motivation we need to keep going1. When we’re doing something we enjoy and feel like we’re making progress, we naturally want to keep going. It’s like a positive feedback loop that keeps building on itself.

Think about it: we’re all more likely to put time and effort into things we actually enjoy, and that effort helps us improve, which makes the whole experience even better. Athletes are a great example; when they win a competition, their confidence increases, which motivates them to train harder and improve even more. The same goes for musicians or artists who love what they do. That enjoyment fuels their practice, helping them grow and get even more out of their craft.

Understanding this upward spiral has completely changed the way I think about teaching and learning languages. It’s all about finding those small wins and building momentum.

Approaching Language Learning as an Upward Spiral

Language learning is a long journey, and let’s be honest, it’s often uncomfortable. Success usually depends on finding ways to stick with it over time, and that can look different for everyone. That’s why it’s so important to focus on building positive momentum.

When we start to enjoy the learning process itself, staying consistent becomes much easier, and that’s what helps us reach our goals.

You might find that building momentum is easier when you engage with the language in ways that feel meaningful to you (autonomy) and creating opportunities to experience success (competence). With regular, intentional practice, this cycle of engagement strengthens confidence, promotes progress, and leads to lasting results.

For me, incorporating simple and quick practice activities, such as writing in a journal, has been a great way to achieve small wins and keep my motivation high as I work on improving my French.

What about you? Have you experienced a turning point in your language learning journey? I’d love to hear your story! If this post resonated with you, share it with others who might find it helpful, or subscribe to stay part of the conversation.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L., 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), p.68.

I love this story. And I'm so glad you didn't give her a sticker or some other external validation, that her being able to complete the task was the reward itself.

I love the idea of helping a reluctant starter build momentum 😍